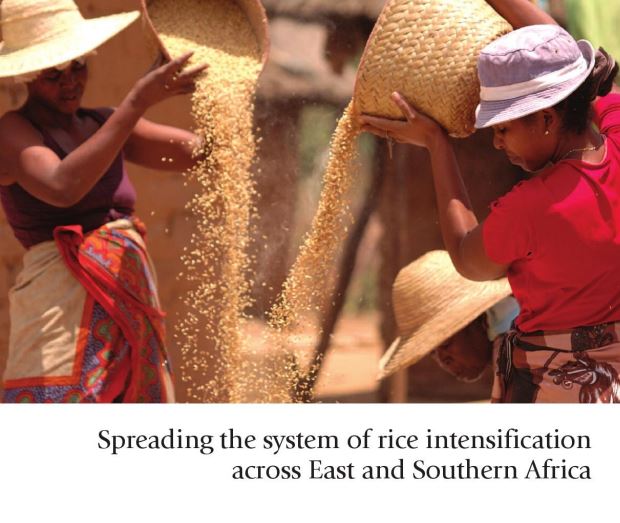

Spreading the system of rice intensification across East and Southern Africa

Rice is the staple food for many countries across the developing world, particularly in Asia, Latin

America and Africa. It fulfils the food energy needs of around half of the world’s population.

1 In

sub-Saharan Africa, where 93 per cent of farm land is rain-fed, rice is a good crop alternative

due to its ability to be cultivated during the wet season. Nevertheless, rice yields are severely

affected by the weather fluctuations of the rain-fed ecosystems. Drought, flooding and unstable

and extreme temperatures threaten the productivity of rice fields and the quality of grains.

In many East and Southern African countries, rice is a staple food for rural households.

Increasing rice production is one of the most powerful pathways to improve household food

security and reduce rural poverty.

In the 1980s, a Jesuit priest living in Madagascar discovered a new way of farming rice that

significantly increased production. This new System of Rice Intensification (SRI) aimed to revive

the natural growth potential of rice through a set of good practices that question traditional

farming methods. In particular, with this new system, fields are not kept flooded. The soil is kept

alternately dry or wet, allowing the plants’ roots to take oxygen from the ground surface. In this

way less water and fewer seeds are needed to produce the same quantity of rice. Seedlings are

transplanted while very young from the nursery to the field, one by one, in square patterns to

allow spacing between rice plants. In addition, the use of organic fertilizers combined with SRI

practices is recommended as in many cases it gives even better results than chemical fertilizers.

The reduced need for inputs (such as water, seed and chemical fertilizer) makes SRI affordable

to poor smallholders, and its successes enhance its potential for replication.

In 1997, after the food crisis in Madagascar, IFAD introduced SRI in its projects in the country,

starting with the Projet de Mise en Valeur du Haut Bassin du Mandraré (Upper Mandraré Basin

Development Project – PHBM). The project successfully rehabilitated the Mandraré inlandvalley lowlands by improving rural infrastructure and promoting the adoption of SRI practices.

From Madagascar, SRI was brought to Rwanda and then to Burundi. IFAD and the Malagasy

non-governmental organization (NGO) Tefy Saina, founded by SRI’s pioneer, promoted the new

set of practices among farmers and facilitated its dissemination through training visits across

borders.

Despite its very good results, SRI is still seen as a risky practice by some farmers, and its success

has not spread as quickly as expected, particularly in Madagascar. The mind-set there still clings

to traditional practices for different reasons. One of them is the perception of a bigger workload

for farmers who take up SRI practices. This is actually true, at least in the initial stages of

adoption. However, once farmers gain familiarity with the new techniques, form farmer groups

or associations, and start using mechanical tools, the individual workload for SRI decreases

significantly. Often households do not have enough labour available from family members and

cannot afford to pay external workers. Therefore, they remain wary of any practices that may

require additional labour resources. Other barriers can be scarce access to fertilizers (organic,

mineral or chemical) and inadequate irrigation infrastructure, which does not allow for careful

water management in SRI’s fields..

Article source: https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/39135645/SRI%20case%20study.pdf/fb791e52-e01f-4812-93d7-19b43edc6c2c